On Friday morning, less than two days after the end of Lecretia’s hearing, we woke and began the task of getting Lecretia out of bed to begin her morning routine. However, despite being awake and lucid, her paralysis had taken a firm grip on her whole body, and she had become as rigid as a plank, unable to bend at the waist. Her brother and I worked to lift her together, and almost had to force her to bend so that she could get into a seated position.

On Friday morning, less than two days after the end of Lecretia’s hearing, we woke and began the task of getting Lecretia out of bed to begin her morning routine. However, despite being awake and lucid, her paralysis had taken a firm grip on her whole body, and she had become as rigid as a plank, unable to bend at the waist. Her brother and I worked to lift her together, and almost had to force her to bend so that she could get into a seated position.

We took delivery of a hoist that morning but when the hospice doctor saw Lecretia at lunchtime, he said that what she really needed was a hospital bed. This was duly organised, but coming into the long weekend meant that the delivery driver got his message late in the day and no doubt had plans for the weekend other than answering calls and driving a bed all the way back to us from the Hutt Valley.

Further calls to the delivery company on Saturday morning were fruitless. One of the nurses, sharing our frustration, went above and beyond and organised for us to be able to pick up a bed from the hospital if we could organise our own transport. If that hadn’t have happened, I have no doubt we would have ended up with Lecretia needing to be moved out of her home and into either the hospital or the hospice via ambulance so that she could be comfortable, which would have been against her wishes. Lecretia’s friend Angela helped me and her brother Jeremy pick up the bed and put it in the back of her SUV. Once it arrived, it took a good hour to figure out how to put it together.

Thankfully, by early Saturday evening, and through the generosity of the district nurses pulling strings on a long weekend, we had Lecretia settled in a hospital bed in our living room, able to be elevated or moved to her side and so on.

I am not relaying these facts to be critical. I am hugely grateful that between hospice, the DHB and ourselves were able to work together to get a good result for Lecretia, but I have to admit it was pretty stressful. It would have been a struggle for someone without Lecretia’s strong support network.

Lecretia is not well. Her eyes are closed most of the time. She is having trouble swallowing. She is talking less and less. But she is facing all of this without complaint. She says she has no pain, and she has not taken any painkillers. This morning she ate feijoas, like the ones from her parents’ home in Tauranga. She is laying in her bed with a quilt sewn for her by a friend who worked with her at the Law Commission. Our cat, Ferdinand, has been sharing her bed with her, laying in her lap, or at the end of the bed.

I’ve been holding her hand and talking about holidays we’ve taken together. Things we’ve seen and done and food we’ve eaten. One of her favourite memories was floating in the lagoon at Aitutaki in the Cook Islands. I describe it to her: the sand, the smell of sunscreen, the salt in the air, the warmth of the sun and the water. The sense of our time there being lazy and long and as vast as an ocean. It makes her smile.

Sometimes she says to me ‘let’s go’. I’ll ask where and she’ll say ‘anywhere’. She wants me to get her in the car and start driving. As though her illness is tied to this place and that if we got far enough away from it she could cast it off like a veil. I wish that were true.

Every so often a tremor comes. Her whole body shakes and vibrates. The pressure of the tumour on her brain stem is causing her brain to reconfigure, to shift against itself like restless earth, causing her body to tremble, the frame of the bed shaking and rattling. And then it subsides, and she rests.

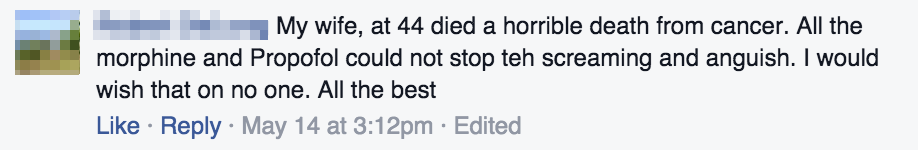

Lecretia’s choice is imminent, and we don’t know yet if she will get to make it. She’s been through a few things already that she would rather not have had to go through, but she has taken all of this in her stride and with as much grace and dignity as she can muster. Would she have chosen to go already if she’d had the choice? Surrounded by love and support like she has been, I doubt it. But she doesn’t know what is yet to come, and what she will have to endure, and that must be terrifying. I know that having the ability to make a choice about how her life ends would give her more strength to face it.

It scares me that in not having the choice she had to consider suicide because she had no certainty or control as she headed into the unknown. Because these moments we are having now are so precious and we would have lost them. I feel for those families who have lost loved ones early because those loved ones weren’t allowed to have the death they wanted.

She is facing this as she faces all things: with tremendous bravery and courage. I am so proud of her. I love her so much. I don’t know what she will ultimately choose, or even whether she will get to. But for Lecretia, it was always having the choice that mattered, not the choice itself. We are hoping for a judgement that acknowledges and respects Lecretia’s free will and autonomy over her own life; the ability to decide how she lives it and how it ends. That is all she wants.

It’s a big day tomorrow, and we have been looking forward to it now for weeks. Lecretia would like to be in the courtroom for the beginning of the proceedings, but I have my doubts as to whether that will be possible. I am sure she will be there for part of the day at least, but as to when and for how long it’s a little hard to say.

It’s a big day tomorrow, and we have been looking forward to it now for weeks. Lecretia would like to be in the courtroom for the beginning of the proceedings, but I have my doubts as to whether that will be possible. I am sure she will be there for part of the day at least, but as to when and for how long it’s a little hard to say.

Aside from a secondment to the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet in 2010, Lecretia has worked at the Law Commission since 2007, project leading a number of reform projects, including

Aside from a secondment to the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet in 2010, Lecretia has worked at the Law Commission since 2007, project leading a number of reform projects, including

Despite the best efforts of modern medicine, cancer remains, for the most part, incurable. Even when we beat it back and it enters what’s called remission, its essence abides in the twists and turns of our chromosomes, waiting for the slightest defect in the intricate machinery of our cells to let it burst forth like a dark flower. Siddhartha Mukherjee in his excellent book

Despite the best efforts of modern medicine, cancer remains, for the most part, incurable. Even when we beat it back and it enters what’s called remission, its essence abides in the twists and turns of our chromosomes, waiting for the slightest defect in the intricate machinery of our cells to let it burst forth like a dark flower. Siddhartha Mukherjee in his excellent book