Lecretia’s most telling symptom, and the one she’s struggled with the longest, is something called homonymous hemianopsia. It means that she is blind in one side of her field of vision. In her case, it’s her left side.

It’s an inconvenient affliction, but also a fascinating one, which reveals a little of the inner workings of the human brain. Lecretia’s tumour is on her right-hand side but the contrariwise nature of the brain’s hemispheres means that damage to the right-hand side of the brain affects the left-hand side of the body, and vice versa. There is nothing wrong with Lecretia’s eyes. They are both in working order and she can see through either of them if the other is blocked. But her visual cortex is ravaged by cancer, so although a full picture is being passed through her optic nerve, her internal screen is only capable of processing the right-hand half of the image.

What this means for her in practice is something called hemispatial neglect. In some ways, the left hand side of her world doesn’t exist for her. I notice that if people approach her on her left, and talk to her, she might ignore them altogether, even if she hears them perfectly well. When she walks around the house, she frequently bumps into things with the left side of her body, because she doesn’t register the presence of objects in her path if they are on her left. You’d think a person with this condition would compensate, that having the knowledge that you aren’t seeing your left side would mean you’d become conscious of that lack of awareness and you’d turn your head to pick up the things you were missing on your left. But in reality that doesn’t happen. Lecretia’s brain tricks her into thinking she is seeing everything she needs to see.

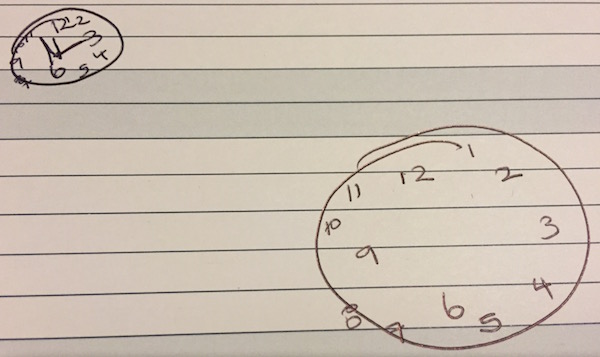

I asked Lecretia to draw two clock faces. Notice how the right hand side is fine, while the left on both is distorted and scattered. This is commonly seen in people with hemispatial neglect.

When we have dinner, she will eat the right hand half of the food on her plate. When she’s done, I reach across the table and turn her plate 180° to reveal the half she’s ignored, and then she eats that. Our cat has figured out exactly what’s going on, and he will invariably approach Lecretia from her left side, and if I’m not quick enough, he’ll successfully steal food from her without her noticing. When she reads a page, if she’s not careful, she will often ignore the left hand words and lose track of what she’s reading. If she’s looking at two columns of items, such as on a restaurant menu, she’ll ignore the left column. And whenever she’s lost something – she is forever losing things – usually it will be in front of her, on her left, and she just hasn’t seen it. “I don’t have a fork,” is a common complaint at dinner. None of this was obvious before Lecretia’s diagnosis, and if it were a factor it would have been a much more subtle symptom than it is now.

In late 2010, when Lecretia was in good health, she was driving home one night alone from a night-class in Newlands. The weather was terrible, it was dark, and as she approached a slight bend in the road, she hit a parked car on the left-hand side of her, totalling her car and doing a lot of damage to the other. She walked away shaken but unharmed. A nearby resident said it had happened before on that bend. I taxied out and picked her up from a good samaritan’s house on Newlands Road, and we took a taxi back home again, while our car was towed away.

As the days followed, we explained it away as a genuine accident. The conditions, the location, the fact it could have happened to anyone. We didn’t look deeper, didn’t see what else might have been right in front of us. I wish I had been more aware of what we might not have been seeing. Was it possible this was the first sign something wasn’t right? We might have got Lecretia diagnosed sooner, got her treated sooner, got the whole damn thing resected. If I were a neurologist, I suppose, I might have noticed something was amiss. But I didn’t notice, and here we are. And I know that now and for years to come, I will always wonder if things could have turned out differently, if I hadn’t been so blind.